3 Mindfulness Habits for a Successful New Year

The new year is coming, and with it comes a host of resolutions that many people are hoping they can fulfill before the end of the year. One of the best ways to make changes in your life is to develop new helpful habits.

A sense of mindfulness will help you work through your problems more efficiently, build yourself up, and increase your chances of success well into the new year.

We are going to look at some mindful habits you can start applying to your everyday life, including your work life, to help you become more productive this year.

Identify where you can improve.The first step to developing mindful habits is to break your bad habits. Think carefully about the things in your life you want to change. Are you trying to quit smoking? Do you want to try and buy a home? Are you looking to expand your business?

Whatever your dream, take some time to consider what you need to change in order to work toward these improvements. Psychology Today concluded that the first two steps to improving your life and changing bad habits are

1. Acknowledging that you want to change while convincing yourself that you're capable of changing

2. Gaining insight into what is causing the toxic habit

Once you are able to pinpoint areas of opportunity, you can start making proactive changes to live a happier, more productive year.

Focus on progress, not the end goal.We've all heard people say that results are the only thing that matter, but that doesn't necessarily seem to be true anymore, at least as it relates to the human mind and the path for betterment. We all think about life in broad strokes, "One day I’m going to own my own house and have a million-dollar-a-year business."

Sounds promising, right?

The truth is, it's much more mindful to focus on the process as opposed to the end goal. Instead of being disappointed that you don't have enough money in your account to buy a house yet, be proud that you managed to save a healthy chunk of change and that you're closer to your goal than you were the year before.

Don't stress because your business isn't profiting a million dollars after the first year. Instead, acknowledge that you've made leaps and bounds, you've grown your business profits, and realize that this is something you should be proud of.

Learn to ease up on yourself.We are our own worst enemy when it comes to critiquing ourselves.

The most important thing to remember is that there are things you can control, and there are things that you can't. Don't beat yourself up over things that you have absolutely no control over. Instead, focus proactively on the things in your life that you can change.

As you may have suspected, this leads back to your habits and how you measure your idea of success. Work toward your goals, and if you make a mistake, acknowledge it, learn from it, and take what you learned from your error with you on your journey.

The key to being mindful is self-awareness. We live in a fast-paced environment where things, people, and ideas can come and go in a matter of minutes, hours or days. Instead of dwelling on everything that goes wrong, shift your focus back to the positive.

At the end of the day, you are in charge of your own destiny. You're capable of making or breaking your new year. Do the right thing. Choose productive self-assessment and care. You deserve it.

It's always best to stay professional, but sometimes professional relationships can benefit from a little humor. The internet is a magical place where anyone with a penchant for the absurd can find what it is they're looking for, whether that means a $24 life-size poster of a senior citizen brushing her teeth or a $76 portable barbecue suitcase. If you run a small business where you're looking to spice up gifts for this year, here are 12 ridiculous ideas we found.

1. Cubii Under Desk Elliptical ($349)

This under desk elliptical comes packed with features like adjustable resistance and Fitbit compatibility. This exercise equipment can provide a great way for employees to work out while they're at their desk and track their progress. It's not clear, however, how in-office workouts will affect productivity.

2. Carrot Pillow ($105)This big carrot pillow is four feet long and a foot wide, making it a weird vegetable-shaped body pillow. Labeled for "loneliness," this carrot is a crazy gift for any employee or home alike. Who knew carrots could provide this level of comfort?

3. Ruggie Alarm Clock ($69.99)The Ruggie Alarm Clock will force your employees out of bed – you have to stand on it to turn it off. This may be a good gift for someone who's notoriously late. There's no telling, though, what a worker will do after they stand on the pad to turn it off (likely go back to sleep).

4. Rachio 3 Smart Lawn Sprinkler Controller ($221.99)In a world where Amazon's voice assistant Alexa is in everything, you can turn on your yard's sprinklers using Alexa. The Rachio 3 Smart Lawn Sprinkler Controller allows you to set schedules, manage your lawn from your smartphone, and skip a cycle if it's rainy or windy. This smart lawn hydration system will cost you, though.

5. The Mug with a Hoop ($25)Yes, this is the exact product name of this weird little mug. The hoop is, presumably, for shooting little marshmallows or other toppings of your choice into your drink. If you have a big basketball fan on staff, this could be a good way to mark him or her. It will certainly stand out in any cabinet.

6. Blankie Tails Shark Blanket for Adults ($37.95)This shark-style blanket is even better than the original Snuggie. Why settle for a regular blanket, when you can get your employee a shark-themed one? We're not sure why this exists, but it might as well go to good use – it's about 6-feet long, making it a good gift for just about anyone.

7. Yodeling Pickle ($13.50)This pickle provides "hours of mindless entertainment," and it comes with batteries included, so you can listen to the beautiful yodeling pickle right when your worker opens it. The wonder of this product is in its mere existence. Happy listening.

8. Gift of Nothing ($6.87)This gift is, quite simply, nothing. Instead of actually getting nothing, you can get this fake version of nothing, which looks like some plastic ball filled with air for just $6.87. This is another winner in the gag gift department.

9. 2019 Bubble Wrap Wall Calendar ($19.90)There's nothing more satisfying than popping bubble wrap. The Bubble Wrap Wall Calendar means your employees will be able to burst a bubble every day for a year, so long as they have the self-control to go one day at a time. While it's great for popping, it may not be the best for scheduling, although it does come with some color-coded stickers.

10. Star Trek Spock Oven Mitt ($23.90)This oven mitt comes in peace, and is a great gift for a co-worker, Trekkie or not. As a tasteful tool to move hot pots and pans around, the Spock Oven Mitt is a funny gift for an employee who needs to keep their hands safe from burns in the kitchen.

11. Bicycle Pizza Cutter ($9.99)Why cut a pizza with a normal cutter when you can use the bicycle version of one? This employee gift comes with a stand and is another bizarre, crazy item for an employee. It also comes in several color options.

12. Pug in a Rug Can Cooler ($25)Get a co-worker a cute pug wrapped in a rug on a can cooler this holiday. You'll be able to keep your drink cold while looking a cute little dog. This item isn't featured on Amazon, but you can pick it up through society6.

It happens all the time. A young startup looking for growth hires a capable marketing agency, and after a few good years, the company has grown to become a small or mid-sized business. With the additional marketing budget, company leadership decides it's time to hire an in-house marketing team.

An in-house team, the thinking goes, can accomplish more with less because the company has more direct control over marketing efforts and fewer dollars are swallowed by agency fees. It sounds good on paper, and sometimes it's the way to go. But it doesn't always work out well.

Research from Forrester and the In-House Agency Forum suggests that in the past decade, there’s been a clear shift from external agencies toward in-house marketing. Just 10 years ago, in-house teams were found among 42 percent of advertisers, but that number has risen to 64 percent. Advertisers say that in-house teams have a deeper understanding of their brands and businesses. Also, they say that in-house teams are faster and more cost-efficient.

These are all good reasons to create in-house teams, but there are still some benefits to keeping an external agency.

The reality is that creating an in-house team is challenging, so small and mid-sized businesses might find that hiring an external marketing agency is the best bet. Here are some things to consider while making this decision:

1. Make sure your marketing professionals have the training they needTo get results, it takes a team of marketers with various disciplines. That means a social media marketer, an email marketer, a content strategist and more. Of course, finding the talent necessary to get results isn't going to be easy. More than 70 percent of creative leaders of in-house teams report that they lack the time to develop new hires, so businesses that go with in-house teams need to ensure their teams have enough support to succeed.

Editor's note: Looking for online marketing help? Fill out the below questionnaire to have our vendor partners contact you about your business's needs.

Businesses can keep their employees on the cutting edge of their specialties with professional development, which should be a key part of the budget. When leaders at Hopper, a flight-booking app, elected to build its own Facebook ad-buying tool, the costs of performing necessary maintenance negated any benefit the tool provided. Other in-house teams might experience a similar skills gap at some point, and 75 percent of marketers feel their lack of expertise is having a negative effect on revenue.

2. Build flexibility into your marketing budgetMarketing budgets are rising. According to a survey of CMOs, budget increases in the past year were 7.1 percent, on average, while the leaders predict 8.9 percent of additional growth in the coming 12 months. Salaries, of course, take up a large portion of the budget. In-house teams can cost almost $600,000 for a full team of marketers. In-house agencies need to build in a cushion in order to respond to unforeseen problems.

Companies that hire external agencies can sometimes operate on a month-to-month basis and purchase individual services as they’re needed, which can be dialed up or down to respond to budget demands. An external agency can also give an organization the flexibility to run various campaigns and experiment with outside-the-box marketing methods. Also, there’s no need for layoffs or new hires with an outside agency.

3. Keep a fresh perspective, and be open to new ideas.In-house teams bring their own notions of how the business operates. They know what it has taken to get the business to where it is, and they’re more familiar with the company’s target audience than a group of outside marketers. That can be valuable and provide shortcuts to get where you want to go.

But sometimes an outside perspective is just what a company needs. In fact, you can have the best of both worlds. It’s common for companies that have in-house teams to still work with an outside agency. The aforementioned CMO survey illustrates that more than 75 percent of in-house teams rely on partnerships with external agencies. A business owner might imagine that an in-house team will be completely self-sufficient, but they might need outside help to do their best work.

For small or mid-sized businesses that haven’t seen great results with an external agency, bringing marketing functions in-house is an investment that could be worth it in the long run. But for businesses that have seen success with an outside agency, it might be better for them to stick to their specialties and hire an external agency to do the same.

When businesses exhibit at trade shows, it's a huge investment – of time, resources and money. The expectation is that after a trade show, the business will be flush with new opportunities, connections and maybe even partnership opportunities.

Yet many exhibitors fall flat at trade shows and start to wonder if it's even worth going to shows anymore. This is because they haven't maximized their impact. Try the following tips for a better trade show experience.

1. Select the best booth location.Within the trade show industry, the physical location of your exhibit is referred to as your trade show booth. As with any business, it's all about location, location, location. Depending on the show and your booth size, you'll want to make sure you're in a high-traffic and highly visible area. This could mean selecting a location at the entrance of the exhibit hall, near a particularly popular brand that will bring higher traffic, or even by food stations.

What you don't want to do is get stuck in the back and wonder why nobody is coming by. Be choosy about your booth location to increase your chances of attracting foot traffic to your booth.

2. Design an impressive exhibit.Whether you're exhibiting in a 10 x 10, 10 x 20 or 20 x 20 trade show booth, you'll want to design something that will stand out in the crowd. An exhibit design house can recommend some budget-friendly but eye-popping elements. This means you'll want to consider where to spend your budget wisely – such as on hanging signage, light boxes, bold graphics, interesting or unique elements, audiovisual elements or props. Whether your budget is hefty or razor-thin, your business must maximize its impact by investing in materials that will draw attention to your brand. You don't have to be an industry giant to make a bold statement that makes people stop and wonder what your business does.

Editor's note: Looking for a trade show display for your business? Fill out the below questionnaire to have our vendor partners contact you with free information.

3. Promote your presence at the trade show.

Most trade shows allow exhibitors the opportunity to buy a list of registered attendees. It behooves your company to buy it so you can start promoting your presence with email marketing. Also work social media and the trade show's hashtags, industry terms and more to get in front of the people you want to stop by your booth. Don't forget to email and call clients and prospects as well. Odds are they'll have someone going to that show and you can touch base with them.

Ideally, you should begin promoting your presence a few months before the show. You can promote in conjunction with targeted pay-per-click advertising campaigns, website promotions and more. The idea is to reach as many people as you can to ensure your booth is full. A full booth makes people wonder what's going on and encourages even more foot traffic to your business.

4. Drum up interest with a giveaway.Giveaways are very popular and a great way to attract more people to your booth. Depending on your industry, you may want to consider some more impressive prizes than just another iPad. For example, at nursing shows, brand-name purses are popular draws for CNOs. At tech shows, the latest and greatest gadgets always attract interest, but so could tickets to a local adventure for while the attendees are in town.

No matter your industry, thinking outside the box can help you to draw more foot traffic to your trade show booth. Nobody wants to stop by and grab your pens or brochure. Instead, invest in a great giveaway and pair it with an interesting way to win. Make sure to stipulate that entrants must be present at a specific day and time to win. This incentivizes them to come back to your booth, exposing them to your brand yet again.

5. Offer food and beverages.If you've ever been to a trade show, you know the sheer amount of walking alone can make you work up an appetite. To draw more people to your trade show booth over another, try offering coffee and bagels in the morning, obtained through onsite craft services. Remember, many trade shows insist that is the only way you can provide food or beverages, or they might bill you for far more than anything you would've paid to bring food to the show. If you've got the budget, host a happy hour in your booth on the first day of the show. Ask to provide drinks on consumption so you don't end up paying an exorbitant cost.

6. Get your staff excited.One of the best ways to maximize your trade show impact is to get energetic people who draw others to your trade show booth. They don't have to be carnival barkers, but a friendly "Hello, how's your day?" is often enough to get someone to stop and take an interest. Their enthusiasm should be palpable, because nobody wants to drop by a booth with a bunch of Debbie Downers. That just doesn't look or feel inviting. Instead, bring excited team members, after training them on reaching out to people on the trade show floor to encourage them to visit your booth.

There are many ways to maximize your impact at a trade show, but with these best practices, you should be able to make a more memorable impression.

Free download, compliments of:

Free download, compliments of:

The forces of the digital revolution have shaken company after company. Industries have been transformed. Entire media and product forms have vanished. Pity the enterprise whose fortunes are tied exclusively to the analog world, be it producing film, renting videos, retailing books, or selling packaged software.

By many rights, one might have expected to find Adobe on the register of companies disrupted by digital. And yet the 35-year-old software developer has persevered. Really, it’s done more than that. Adobe has excelled, and it has done so by embracing the very technological forces think cloud, mobile, platforms, IoT that could very well have been the harbingers of demise for a legacy producer of packaged software designed for the desktop.

Adobe exceeded $100 billion in market cap and joined the Fortune 400 for the first time in 2018, while ranking No. 13 on Forbes’ Most Innovative Companies list. Adobe Chairman and CEO Shantanu Narayen found himself similarly positioned on Glassdoor’s list of top CEOs of large U.S. companies.

In conversations via videoconference and email, MIT Sloan Management Review editor in chief Paul Michelman asked Narayen to share his thoughts on nine key words related to Adobe’s journey.

Narayen: Adobe’s mission is to change the world through digital experiences and, in that context, we have two strategic initiatives: empowering people to create and helping businesses transform.

The world without creativity would be a really boring place. We think everybody has a story to tell. We enable people to tell their stories by connecting them with the right technology at the right time with the right intuitive interface.

Look at an area like education, where there’s a lot of talk about the importance of STEM. That’s true. But we like to talk about STEAM. In addition to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, the arts are an important part of what makes not just education but the entire world such a special place.

I also think you attract the best and retain the best when people connect with the mission and respect the values that you have as a company. Our mission enables us to attract and retain a very talented work base that looks at the role of creativity in enabling people to tell their stories with a lot of pride.

Narayen: Every decade or so, there seem to be big, tectonic shifts in technology. The technology companies that have grown, matured, and thrived recognize these shifts and figure out how to harness them toward whatever mission that they are following.

The cloud and mobile led such a shift in recent years. With the cloud, we saw we could enable two crucial advantages for our customers: location independence and collaboration. Put yourself in the shoes of a creative professional and consider the tools they use every day to do their job. Why shouldn’t all of their assets their project files, fonts, brushes, and presets be at their fingertips at all times? It’s possible with the cloud.

Mobile similarly pushed us to ask, Why should people need to be tethered to a desk in order to create? At Adobe, we immediately began exploring ways that our flagship products like Photoshop and Acrobat/PDF could work better on mobile devices. We introduced several new mobile-first apps as well. We firmly believe that mobile devices can be used for creation and not just consumption.

I think we do a good job looking at shifts in technology and asking ourselves, “What is the power for Adobe?”

That’s the question we’re asking about AI right now. We look at AI through the lens of community the millions of creative professionals, technology developers, young creatives, and enterprises we work with. If we can harness the power of the community through AI and bring that power back to every individual, there would be something deeply empowering in that.

We are also thinking about the domains that we participate in and how can AI help our technology be more accessible, help us to do things faster, or help automate inefficient processes. For example, we look at imaging and AI and ask, What if we could automatically tag images or search for images based on colors or likeness? Or with digital documents, AI can be used to derive meaning and sentiment from pages and pages of material. It can help spot commonalities and differences across documents. The potential for how AI can improve the way we work and the way we create is huge.

Narayen: We think about platforms in a couple of ways. First, how are we investing in deep technology innovation that will stand the test of time? We want to solve hard problems; investing in a platform is justified if it enables you to solve a hard problem and builds something that will serve customers for many years.

Next, how are we harnessing the power of the community so users can extend and customize what we create? Are we gleaning the intelligence of an entire community?

If you’re Adobe, and you get the platform right, you are serving the entire workflow of a customer. The byproduct of that could be that you’re gaining more market share or you’re considered more mission critical. For instance, we think about how we can be more essential to a magazine not just focusing on content creation but on content delivery and monetization.

Narayen: Thinking holistically about the entire customer experience has become far more important than it was five years ago or even three years ago. Traditional product companies used to think just in terms of functionality and features. Now, you have to consider everything in the ecosystem.

Questions we ask look like: How do you transact business? How do you renew? How do you provide training or access to experts? How do you get feedback? How do you engage with the community? All of these go to either enhancing the customer experience or limiting it. And customer expectations have changed dramatically.

Traditional companies talk a lot about the selling motion but not enough about usage. We have built a data-driven operating model for the creative cloud. It focuses on addressing these key questions about the customer experience.

I think the challenge for a subscription-based business is to recognize that customer acquisition is only the first step. Managing customer satisfaction through the whole process that ultimately leads to renewals is far more important. Every customer is either an evangelist for your product or they’re a detractor, because it’s not just about that one-time purchase any longer, but rather about the ongoing journey and experience. We like to say as a company, retention is the new growth.

Narayen: We had core hypotheses that led us through the transition from a product-oriented business to a subscription model: that we could deliver a better experience long term.

Our hypothesis stated that understanding how people are using our products online would enable us to tailor our offerings quicker than the traditional 12- or 18-month product development cycles allowed us to do.

We knew that innovating at a faster pace was necessary for long-term success. Yet everything that we had in place at the company at that point was oriented around these artificial boundaries of legacy product cycles.

When you have such strong convictions about how you can innovate faster and serve customers better, it gives you a better foundation to speak to the benefits to the market, in terms of both customers and investors. We needed to help the market understand how our business looked in a subscription model and to provide data that supported our hypothesis that subscriptions would provide true unit growth over perpetual sales.

The second thing we did was to give three-year targets. This wasn’t a case of, “Hey, believe us.” We were transparent with the numbers, both short term and long term. We publicly shared the financial indicators and the time line for transitioning the business.

You have to do flag planting, and you have to do road building. We planted the flag internally to the company and externally, so our employees and customers could see how this transition would work. Our flag was, “Here is what we’re seeking to achieve by moving to subscriptions, and here is why it’s going to be a great thing for our customers and our business.” And then we showed everyone how we were building the road. That road was our time line of what to expect on the journey: the specific product, financial, and customer experience milestones. If we did just one without the other, we could not have had the kind of success that we’ve had.

And we exceeded all of the targets. In our most recent earnings report, approximately 90% of our revenue came from recurring sources, up from approximately 5% prior to moving to a subscription model.

Narayen: The process of transforming to digital and new business models was certainly uncomfortable for us in ways. When you’re trying to innovate and tackle a major transition, it can feel impossible to connect all the dots from where you are to where you want to go, which is why you have to reinforce the positives. You have to learn to adapt to the things that you may not have gotten right. You have to create a culture that enables you to look at things with transparency, acknowledge failures, and course-correct.

We had already established a culture of experimentation in Australia, so we did a lot of experiments for the new model there. We offered similar products under both a subscription model and our traditional model in that market, and then monitored the uptake. We found that we were bringing in a lot of new users under the subscription model, which addressed one goal we set for the business: growing our base. In addition, many existing customers told us they would not have upgraded without the subscription offering. The trial in Australia backed our hypotheses and gave us even more confidence that the new model would be the right move for our business and our customers.

The leaders who thrived in the transition were the ones who got comfortable with ambiguity and uncertainty. Then our job as managers is to protect employees from a lot of the negative effects that uncertainty and ambiguity can bring and also help them understand how they can adapt in an uncertain environment.

In management, you have to get far more comfortable with the unknowns. Rarely will somebody come to a senior manager and say, We’re all unbelievably aligned, and this is what we should do. Do you agree with us? They typically come when there’s uncertainty or when there are differing opinions. Dealing with uncertainty forced different behaviors at Adobe. These included becoming more comfortable taking chances and being OK with small failures. It also fostered more communication.

The fun part about big transitions, if you create a learning culture and people are intellectually curious, is that they turn out to be the times when you grow the most in your career, because you’re not just shepherding an existing thing you’re creating a new path.

Narayen: I prefer the word investments. Risk sometimes suggests irresponsible behavior.

I’m very comfortable with making investments. You have a core hypothesis. You have data to support that hypothesis and guide the process. Some of these investments succeed and some don’t. This goes hand in hand with creating a culture that can celebrate failures as well as successes. When you do this, people are more comfortable trying new ideas even when some of those ideas don’t pan out.

Narayen: It’s insane to me that people think that drawing with a mouse is an intuitive way of interacting with a computer. We look at voice as a natural interface and a great enabler to help people do things. So, we’re looking at ways to unleash creative capabilities through new modalities: voice, touch, stylus, and more. The mouse and keyboard still have their place. But creativity demands more flexibility.

Narayen: One of my favorite expressions is “preserving the status quo is not a business strategy.” That’s something that I use to emphasize the need for constant reinvention.

I think we all have to focus on the storytelling aspects of what we are trying to accomplish and to bring color to what we want to do. I’ve worked at that aspect of my role, personalizing and creating narratives that people can engage with.

What’s been unbelievably rewarding and exciting about this journey is the focus on team and acknowledging our accomplishments as a team. When things go well, the CEO gets way too much credit, and when things go badly, the CEO gets too little blame.

I’ve been fortunate to have a senior leadership team that’s stayed in place for many years and a board that understands that taking the long-range view is the only way to build sustainable and resilient companies. People ask a lot about how we had the courage to make such a big transition. Our shared vision as a team about what we needed to accomplish and how we would go about doing it was so powerful that it often didn’t seem like we needed all that much courage.

India Cloud, China Cloud, U.K. Cloud, and U.S. Cloud — it may not be long before we are talking about country-specific cloud technology. Until now, the spotlight has been on cloud providers — Microsoft, IBM, Amazon, Google, Alibaba — and their generic and industry-specific capabilities. Data localization has often been considered an afterthought, but this issue is one that enterprises must consider in their cloud computing strategy as they invest and innovate with emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, internet of things (IoT), and blockchain. As governments around the world begin mandating data localization laws, organizations will need to address the wide-ranging implications in strategic ways as part of their national cyber policies.

Recently passed regulations in the European Union around data privacy, such as the General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679 (GDPR), have pushed cloud providers and enterprises to implement data storage in local servers and encryption requirements in their products and services. Outside of Europe, especially in Asia (with the noted exception of China, which has rigid localization laws), data localization has mostly been a passive issue. With India’s recent aggressive push to pass data localization laws, it’s just a matter of time before other emerging economies accelerate similar policy measures, as data and cyberspace become the next frontiers of innovation, competitiveness, trade, and foreign policy levers among nations.

Democratically elected governments around the world will be abdicating their responsibility if they don’t have control over the data originating within their sovereign borders to address problems of national interests and crime. Recently, when the government of India circulated a policy document that described its plans to mandate that cloud providers and multinational companies operating in India store data generated from transactions and interactions with its citizens in locally hosted servers, the reaction from the global companies and cloud providers was collective criticism and backlash. The policy was criticized as a barrier to global trade and innovation. However, recent noteworthy data breach events, whether Cambridge Analytica, Wikileaks, or even the continued spreading of fake news on social media platforms, have raised the call for firmer policies around data protection. The remaining question may be where the line of privacy and localization should be drawn for governments, organizations, and consumers.

In an effort to future-proof against possible localization outcomes, there are five focus areas that global organizations should address when assessing their enterprise cloud strategy:

Industry and global context. Companies should assess cloud vendors based on a set of business and technical dimensions on their industry and global context. Organizations are increasingly considering global, multi-cloud strategies due to conflict of interests, privacy concerns, country-specific capabilities, and cost leverage. For example, the retail and consumer goods industry has become increasingly uneasy with Amazon Web Services (AWS) due to concerns over competitive advantage. Global IT governance. The IT operating model will become more decentralized and complex across the global landscape. This will require the right organizational structure, autonomy, and tighter coordination through a global operating council of technology leaders. At PwC, the global council of technology leaders meets at least once per quarter every year to share lessons learned, leading practices, and reusable assets to tackle digital challenges. Global interoperability and reusability. Cloud computing standards should not be designed as “one size fits all” but rather as a tiered approach where global, regional, and local templates, software code, and algorithms can be applied based on country-specific regulations. For example, one might ask: What is required for an AI application deployed in the United States to be reused in a cloud environment in Europe or Asia with minimal changes? Privacy and security standards. Keeping track of privacy and security rules at the country level and implementing controls on the cloud is an onerous task. Enterprises should institute a global privacy organization with autonomy at the country level to implement local privacy policies and templates on the cloud. Facebook was recently fined by the European Union over privacy violations and has taken steps to build a dedicated privacy organization and automate privacy controls. Data access controls. Global cloud applications need appropriate security controls and audit logs to track data access patterns as data storage, computing, and consumption shift from a shared global instance to a local mode. As data becomes more of a monetization asset, the risk becomes whether it might end up in the wrong hands by theft and misuse.This new era of data localization regulations will also affect cloud providers and impose margin pressures on their business as they ramp up their capital spending to develop new cloud infrastructures within each country and deploy local services and personnel to comply with new regulations. This will, in turn, have a ripple effect on global enterprises in terms of cost effectiveness, quality of service, and innovation as they leverage cloud platforms.

As equally affected stakeholders, global enterprise, digital transformation, and cloud business leaders should work together with local governments and technology councils in their regions to educate and influence commonsense cyber policies and laws. In the future, it will continue to be crucial that regulations protect user privacy but also support a global growth trajectory without hindering the momentum of the digital economy.

Free download, compliments of:

Free download, compliments of:

Who are the kings of R&D spending? High tech and health care, of course. These sectors each account for nearly one-quarter of global R&D.1 Consumer goods companies? They’re near the bottom, at just less than 3%.2 But what they do spend is hardly trivial. The largest consumer goods companies each lay out more than $1 billion annually. Spending by one of the biggest, Procter & Gamble, has averaged about $2 billion per year for the past decade.3

What have these behemoths gotten in return for their hefty R&D outlays? Virtually nothing from a sales perspective. In an industry analysis, we found that the consumer packaged goods sector’s biggest R&D spenders saw no appreciable impact on revenue. That’s troubling for companies whose growth has plateaued over the past five years, as new competitors have challenged established brands.

At the company level, however, the picture is more nuanced: Even though (true to the industry average) companies that spent heavily on R&D — such as P&G and Unilever — saw no measurable impact on sales, some outfits that spent less on R&D showed a significant positive correlation. For example, Henkel and Beiersdorf, both in Germany, enjoyed a revenue boost, as did L’Oreal of France and Reckitt Benckiser in the United Kingdom. We’d term Henkel and L’Oreal, which have roots in the chemical industry, as medium spenders and the others as modest spenders.

It turns out, as economist E.F. Schumacher wrote, small really can be beautiful.4 Of course, incremental innovation — reaping healthy returns with small, iterative improvements — isn’t a new idea. Apple has famously boosted sales of its iPhones with incremental tweaks in each product cycle, and brand-name prescription drugs sometimes offer modest upgrades over prior treatments or generic alternatives. But conventional management wisdom, based on years of research, still holds that R&D productivity depends on industrial might: Big companies can spend more on innovation, and as a result, they innovate more — and better.5 In the consumer products world, at least, our analysis suggests that’s not the case.

Different Spending PatternsTo better understand this puzzle, let’s examine two consumer goods companies with starkly different levels of investment in R&D: P&G and Reckitt Benckiser.

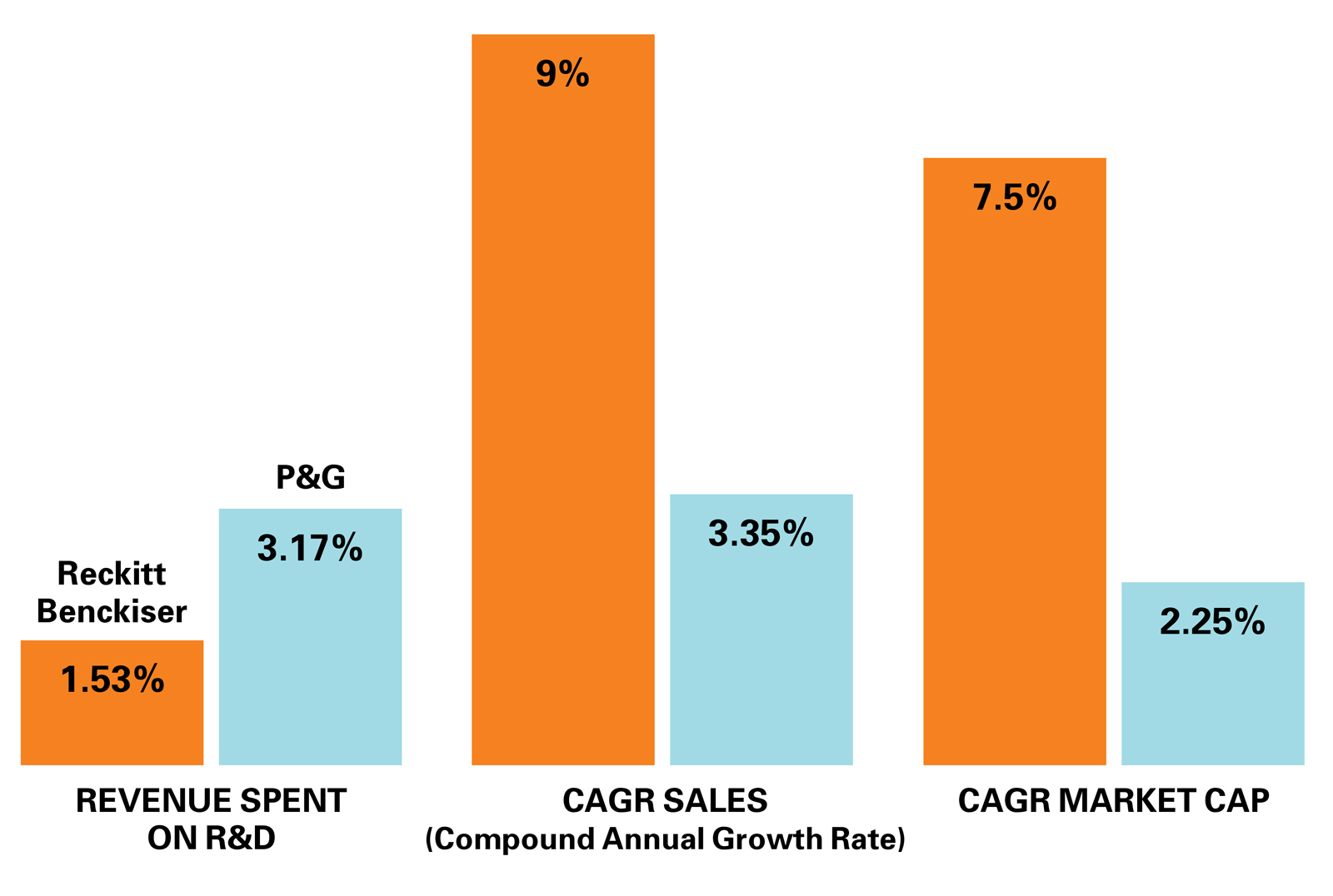

Despite P&G’s huge R&D investment — more than $38 billion from 1998 to 2017, compared with Reckitt Benckiser’s $2 billion over the same period — P&G’s outlay has reaped fewer rewards on a key measure: While P&G spent more than 3% of its annual revenue on R&D compared with 1.5% for Reckitt Benckiser, P&G’s sales grew at a compound annual rate of 3.4% while Reckitt Benckiser’s sales grew almost three times faster, at 9% per year. (See “How Judicious R&D Spending Can Pay Off.”) What’s more, P&G has introduced no blockbuster brands since its Swiffer dusters and mops debuted almost 20 years ago.6 (See “Big Investments Don’t Always Yield Big Returns.”) Certainly, a company can succeed at R&D without creating new household names, and large consumer goods companies have generated plenty of patents while reducing the cost and increasing the shelf life and convenience of their products. But given P&G’s R&D spending and its history of developing famed brands like Tide laundry detergent, Crest toothpaste, and Dawn dishwashing liquid, it’s surprising that its blockbuster innovation has stalled.

From 1998 to 2017, Reckitt Benckiser spent a much smaller portion of revenues on R&D than Procter & Gamble did — but grew sales much faster.

Source: Datastream and Reuters data services

P&G has not created a meaningful new brand since Swiffer, almost 20 years ago.

Source: Trian Partners, white paper on P&G innovation, Sept. 6, 2017

The diverging innovative fortunes of Reckitt Benckiser and P&G can be glimpsed in their stock prices as well. From 1998 to 2017, P&G’s share price increased by only 2.5 times, while Reckitt Benckiser’s shares increased more than sevenfold.7 A number of factors beyond R&D spending and innovation could have contributed to the companies’ valuations. That’s why we modeled sales as a function of multiple factors. (See “About the Research.”) Still, investors’ conviction about a company depends largely on expectations about its ability to generate sales and growth via strong returns from innovation.

This article draws on two main data sources. The first is a recent data set published by the European Economic Community aimed at measuring the R&D effectiveness of 2,500 companies across industries and countries. We complemented this with marketing data, stretching from 1989 to 2016, from Compustat. For the companies we examined, we modeled sales, using a Cobb-Douglas production function, as dependent on labor and capital — the traditional inputs. But we added two other inputs, R&D and marketing investments, so we could measure the contribution of each factor to sales.

At the industry level, when we analyzed sales results for consumer goods companies, we found, on average, a strong positive correlation with marketing investments but virtually none with R&D spending. In contrast, sales in the pharmaceutical industry, which we included as a benchmark, showed strong positive correlations with both marketing and R&D.

However, our analysis at the company level shows that the lack of R&D impact in the consumer goods sector does not hold across the board. Some of the companies that made smaller, more targeted R&D investments saw significant sales gains; the biggest spenders were the ones that yielded no appreciable returns.

How do we explain our findings? One factor may be that P&G and Reckitt Benckiser seem to embody different philosophies of innovation.

We see the approach favored by big consumer goods companies like P&G and Unilever as analogous to Isaac Newton’s third law: They behave as if for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. In other words, they expect big returns from big investments, so they chase blockbusters. But, despite lavishing money on R&D, P&G has produced no more Swiffers.

Contrast that with what we call a Lorenzian approach to R&D investment, which has parallels to the work of MIT mathematician Edward Lorenz, the father of chaos theory. When examining weather patterns, Lorenz discovered that small actions could have large consequences. A butterfly flapping its wings could lead to the formation of a tornado. Like a weather system that amplifies the impact of a fluttering insect, a complex system of companies, customers, competitors, suppliers, and influencers can amplify or diminish the impact of an innovation. In such a world, big ideas can die, and small ones can thrive, as they do at Reckitt Benckiser.

The company doesn’t have a big R&D budget nor a staff of laureled scientists. So it opts to spend small but focus on marginal improvements to its best-selling brands. Reckitt Benckiser starts with deep consumer research to determine how its best brands can be improved and how much more consumers would be willing to pay. From a technical point of view, its innovations are incremental.

Witness the company’s tweaks to Finish, its dishwasher detergent. A few years after launching the product, the company added a rinse agent. It followed a few years later by including salt to soften water and prevent spots and watermarks. And, more recently, it incorporated an ingredient to protect ceramic glazes during washing. While the changes are small, they’re all features that customer research suggests people will value.

Note that Reckitt Benckiser’s approach differs from the standard “versioning” long practiced by big consumer goods companies. Versioning is adding a new model, size, or wrinkle to the base brand in hopes of hitting the next quarter’s sales target or protecting retail shelf space. Thus, consumers are faced with dozens of flavors of potato and tortilla chips and countless varieties of sodas. The problem with this approach is that, even if it works in the short term, over time it can create complexity for the brand owner, especially in production and logistics, and confusion for customers. By contrast, with each product iteration, Reckitt Benckiser looks at the whole line and retires any version that no longer earns its space on the shelf.

Reckitt Benckiser’s R&D projects are less risky and far less costly than those of its bigger competitors. But the company sets an ambitious performance target for each one. It expects a certain percentage of its sales each year to come from new products or better versions of existing ones, and its market-facing executives are rewarded financially when the company hits or exceeds those targets. This pay-for-performance incentive, in turn, motivates the company’s personnel to rally behind R&D-improved products and drive them into the marketplace.8

How Big Spenders Can Improve Their ReturnsSo what’s the solution for big-spending Newtonians if they want a better R&D return? We see three ways they can change their fortunes: become more Lorenzian, “buy in” promising new ideas, or foster greater collaboration between marketing and R&D.

Make more small bets and fewer big ones. If Newtonians are going to continue to spend heavily on R&D (and in many cases, they should), they need to invest better.9 This means cutting back on big bets offering very questionable potential returns. Instead, they should focus on smaller bets that are based on a deep understanding of (1) consumers’ desires, (2) the significant value a small innovation can add, and (3) the system of retailers and competitors in which the innovation will be introduced.

One might ask, “But shouldn’t companies pursue disruptive innovation before they themselves are disrupted out of business?” In the case of consumer goods companies, not necessarily. If a company has a tradition of success through other means, like marketing, it may lack the R&D chops to produce big breakthroughs.

Plus, while it’s true the occasional breakthrough can radically change a market or a company’s fortunes, it’s equally true that such market-shaking innovation doesn’t suddenly just happen. It often results from solving many smaller problems over an extended period, not just one big problem. Apple’s iPhone followed decades of work on microprocessors and cellular technology, and Amazon Go, the online retailer’s new chain of automated brick-and-mortar stores, was built upon prior advances in smartphones, computer vision, and machine learning. Like big scientific breakthroughs that follow seemingly less-consequential discoveries (Einstein’s remarkable theory of relativity drew heavily on non-Euclidean geometry, for instance), these innovations appeared to burst forth as eureka moments but actually rely on decades of work by informal armies of scientists and engineers.

Winning in markets also requires a willingness to identify and seize small gains. The U.K. cycling team offers another instructive example. Heading into the 2012 Olympic Games in London, the team hadn’t been a world power but wanted to medal. Coach Matt Parker, in his role as the team’s “head of marginal gains,” was a proponent of doing little things to gain an edge.10 He encouraged team members to wash their hands carefully and travel with their favorite pillow. The team sprayed alcohol on tires before races to make them stickier and installed a tiny data recorder under every cyclist’s saddle. At competitions, the team used its own transportation to stave off infections. And it fed its cyclists fish oil and Montmorency cherries because such foods are full of antioxidants. These and other seemingly trivial moves added up. Every British track cyclist improved performance between the semifinals and the finals in the 2012 Olympics. More surprising, the U.K. team won 14 track and road medals during the London games, even though it had few stars beforehand.

There’s an analogy here to the now-famous “moneyball” philosophy in baseball, which recognized that the number of base runners a team got per game correlated more strongly with wins than did the number of home runs it hit.11 That insight prompted the pioneer of the concept, Billy Beane, who was then general manager of the Oakland Athletics and is now its executive vice president of baseball operations, to bring in players adept at getting on base, whether through hits or — this was radical thinking at the time — walks. Not coincidentally, these players were far less expensive than home-run sluggers. Beane parlayed his team’s smaller investment into a big payoff: more victories than teams spending twice or three times as much on players. Eventually, the rest of baseball caught up. Today, the use of advanced statistics to evaluate players and seek competitive advantages is common in Major League clubhouses.

Bart Becht, who was CEO of Reckitt Benckiser from 1999 to 2011, sees the parallel in his world: “Innovation is about getting many base hits and occasionally hitting the home run. You very rarely win a baseball game just by hitting home runs.”12

Buy in new ideas. Newtonian companies also should acknowledge that, while they’re adept at developing and commercializing products, their size and organizational structure aren’t ideal for deep research and invention. As Clayton Christensen, the Kim B. Clark professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, points out in his work on disruptive innovation, big companies are often leaders in their sectors and therefore avoid doing anything that threatens the status quo — because they have the most to lose.13

Thus, they should look outside for help. One way to do this is by outsourcing the “R” of R&D, capitalizing on the fact that other companies — those that are smaller, take more risks, and have more of an innovation culture — can produce better ideas. That’s a model long used in the pharmaceutical industry.14 Although they have strong R&D traditions, the biggest drug companies now often leave the early stages of drug discovery to small companies and university labs. Then, when a breakthrough looks promising, they buy up the little innovators or license the discoveries.

A recent deal between Nestlé and Barry Callebaut, a Swiss maker of chocolate products, provides a consumer goods example of the benefits of buying in innovative ideas. Barry Callebaut caused a sensation last year when it introduced what it calls “the fourth chocolate” — a ruby-colored confection that has taken its place alongside the long-established dark, milk, and white varieties. The company devised a way to process red-hued cacao beans into powder while retaining their color. Ruby chocolate is being marketed as the first natural new color for chocolate since Nestlé created white chocolate 80 years ago — in a product category that’s been around for hundreds of years. Aiming to inject new pizzazz into its product line, Nestlé struck a deal with Barry Callebaut to use its ruby chocolate exclusively for six months. Nestlé unveiled the fourth chocolate in a new version of its KitKat bars, which it launched amid great buzz in Japan around Valentine’s Day.15

There’s debate about whether ruby chocolate is a true innovation or just a marketing gimmick. Both sides have their arguments, but the fact remains that the product came from a smaller player that doesn’t own any brands — Barry Callebaut is a private-label manufacturer, not an industry stalwart that splashes out for R&D.

Another way to buy in ideas is to acquire the innovators themselves, not just their innovations. This is what Unilever did when it bought Dollar Shave Club, a subscription-based seller of razors, and what PepsiCo did when it purchased SodaStream, a creator of home soda-making machines. In both instances, the bigger company got the innovations it needed while focusing on what it excelled at: marketing and commercialization.

Get marketing and R&D to cooperate. Finally, Newtonian companies must tackle what’s arguably their biggest innovation challenge: fostering collaboration between their marketing and R&D staffs. There’s ample evidence that, when marketing and R&D cooperate, success is greater than when either dominates.16

Take the high-tech industry, where R&D typically rules and marketing has comparatively little power. Intel, long run by scientists and engineers, is a familiar example.17 It could charge a premium for its processors because they had market-leading performance — the best combination of speed and price. However, a competitor, AMD, figured out how to create processors with the same performance and charge less for them. After suing AMD and losing, Intel foresaw a less profitable future of price wars and commoditization if it stayed on its course. In response, its senior management greenlighted the famous (and expensive) “Intel Inside” branding campaign, which not only created greater awareness of Intel but also differentiated its processors in the minds of computer buyers. Without R&D’s willingness to cede some of its power — and resources — to marketing, Intel would likely be a very different company today.

In consumer goods companies, marketing tends to wield more influence than R&D: Marketing builds powerful brands and creates enormous value for investors. Big players in the industry can’t — and shouldn’t — forget that. But their R&D staffs must step up as well. They need to identify promising new ideas, whether inside or outside the company. And they must become adept at finding attractive candidates for buying in. This will require being more visible in and connected to the R&D and startup communities where the best “R” is happening.

On top of this, R&D must be given a stronger voice. R&D divisions need people to champion new ideas and generate enthusiasm among top-level decision-makers. That will secure resources for further development and commercialization. If managers with those skills aren’t already part of the R&D team, it’s time to develop them or, if necessary, find them elsewhere.

At many large consumer goods companies, a reflexive approach to innovation — just spend more! — is failing to generate sales and growth. Making smaller and more-focused bets, buying in ideas, and aligning R&D and marketing can produce better outcomes for big and small spenders alike. Those tactics are already working well for smaller consumer goods players like Reckitt Benckiser, but Nestlé, Apple, and other large companies are benefiting from them, too. Reaping greater R&D returns requires hard thinking not only about what your company is spending but, more important, how it’s spending.

Free download, compliments of:

Free download, compliments of:

Managers have no shortage of advice on how to achieve organic sales growth through innovation. Prescriptions range from emulating the best practices of innovative companies like Amazon, Starbucks, and 3M to adopting popular concepts such as design thinking, lean startup principles, innovation boot camps, and cocreation with customers. While this well-meant advice has merit, following it without first understanding your company’s innovation narrative is tantamount to going from symptoms to surgery without a diagnosis.

An innovation narrative is an oft-overlooked facet of organizational culture that encapsulates employees’ beliefs about a company’s ability to innovate.1 It serves as a powerful motivator of action or inaction. We find innovation narratives in two basic flavors: growth-affirming and growth-denying, or some combination thereof.

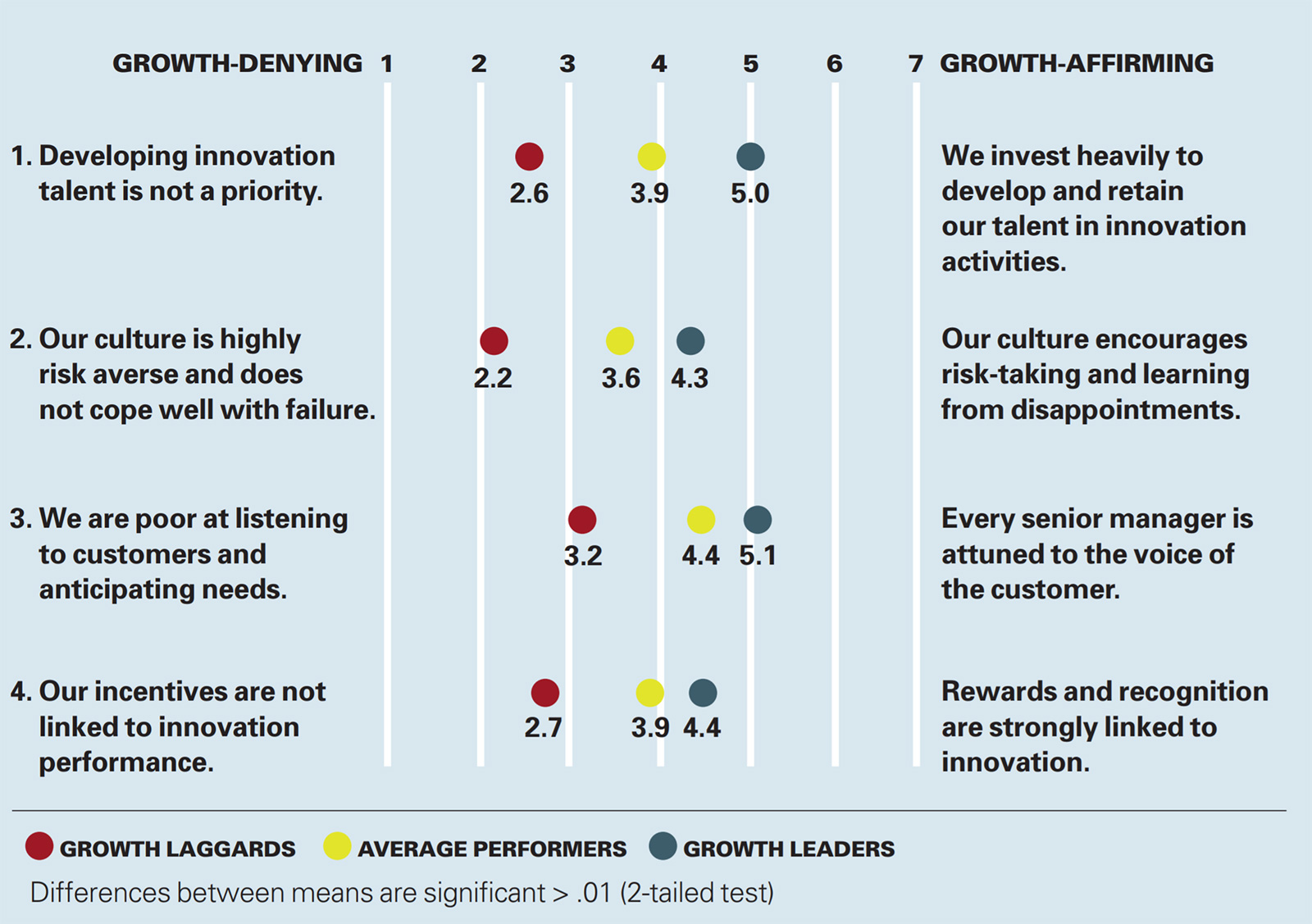

Companies that lead — or aspire to lead — their industries in organic growth need to have a coherent, growth-affirming innovation narrative in place, and we will discuss why that’s important and what it can look like. But what actions support the development and maintenance of such a narrative? To answer that question, we tested 18 possible innovation levers and identified the four that are most relied upon by organic growth leaders to stay ahead of their competitors: (1) invest in innovation talent, (2) encourage prudent risk-taking, (3) adopt a customer-centric innovation process, and (4) align metrics and incentives with innovation activity. We will look at each one in turn.

These four levers will be familiar to innovation practitioners, but their effects intensify with managerial focus. They serve as so-called simple rules.2 That is, they avoid the confusion and dilution of effort that result from trying to pull too many levers at once or in an uncoordinated manner, and they channel and prioritize leaders’ efforts to embed a growth-affirming innovation narrative in their companies.

Identifying Your Company’s Innovation NarrativeOrganizational narratives, and especially innovation narratives, provide a useful means of diagnosing the current operating reality in a company and guiding interventions to sustain or change that reality.3 What is the prevailing innovation narrative in your company? To sort that out, listen to how the people responsible for innovation talk about it and the stories of successes and failures that they tell. Then ask yourself what values and beliefs they are conveying.4

When we spend time with companies that lead their industries in organic growth, we typically find a refreshingly upbeat, constructive, ambitious character to their innovation narratives. These are the kinds of things we hear: “If you want to get ahead, build a new business.… Everyone knows our growth strategy.… Well-intentioned failures are learning opportunities.… If you innovate and it’s not something that benefits the customer, then it’s not innovation.”

Within companies that are growing more slowly than their rivals, the prevailing narrative about innovation is often decidedly discouraging.We hear things like “Immediate needs soak up our innovation resources.… There are no carrots when it comes to innovation, only sticks.… Innovation activities are usually just added to our primary operating responsibilities.”

You can gain further insight into a company’s prevailing innovation narrative by asking the executive team questions such as “Are you confident that the company’s organic growth goals can be reached? Why?” and “Are those goals usually hit or missed? Why?” It is crucial to understand what executives are really saying when they answer. For instance, are they rationalizing the company’s past innovation performance? Are they ascribing that performance to factors and forces outside their control? Those types of responses signal a defensive posture, which can easily undermine growth. But if leaders instead take responsibility for missed goals and say what they are changing to improve future results, they are poised to affirm growth. Then whichever narrative their answers suggest should be tested with an in-depth analysis of a sampling of the company’s innovation initiatives. No narrative should be taken at face value.

When the vice president of development at a large alcoholic beverages company was having difficulty getting senior leaders to support proposals for new products, we worked with her and her team to interview them regarding their beliefs and assumptions about innovation and its returns. What emerged was a picture of a defensive, play-it-safe organization that believed the market was tired of new products and competitors would match one another’s moves. The interviews also revealed a distinct aversion to the uncertainty of innovation and an assumption that once a product is launched, it is too late to fix mistakes. The company’s narrative was growth-denying, and its anemic innovation activities and lack of relevant new products confirmed it.

If you discover that the prevailing innovation narrative in your company is growth-denying and impeding innovation, all is not lost. You can begin to change it by envisioning a desired future state in which the company has become an industry leader in organic growth through innovation.5 Answering these questions can help: If our organization acted out a growth-affirming narrative, what behaviors would we see? What would a storyboard showing “the way innovation works around here” look like? Once you have a growth-affirming narrative in mind, you can turn your attention to bringing it to life within the company.

To identify the most effective levers for organic growth, we conducted a four-stage study, including interviews with 25 innovation leaders and a survey of 192 senior executives, directors, and innovation practitioners from diverse global companies.

Our goal was to determine the effects of 18 popular levers on a dependent variable (an optimally weighted combination of past growth performance, measured by the rate of organic growth relative to competitors in the past five years; present commitments, measured by current spending on innovation activities relative to major competitors; and future growth prospects, measured by the confidence of the leadership team that the organic growth goals for the next three years could be achieved). Then we confirmed our results using a variety of statistical methods, including regression and factor analysis and causal path modeling.i

Bringing a growth-affirming innovation narrative to life is complicated by the sheer number of interventions available to companies. When we examined the existing literature on innovation and analyzed the recommended actions, we found a total of 18 widely touted levers to pull, such as investing in a systematic search for ideas, opening the innovation process to partners, conducting postmortems, and changing the governance structure.6 Attempting to pull this many levers at a time is a prescription for failure in any change initiative — it diffuses managerial efforts and resources, and complicates coordination and implementation. But without a clear sense of what really works, organizations may be tempted to try a little bit of everything. They need help narrowing the field of possibilities.

In our study, we found that only four of the 18 innovation levers consistently and significantly set organic growth leaders apart from growth laggards and average performers. (See “About the Research” and “Profiling Growth Leaders.”)

The following four levers — and associated behaviors — can support a growth-affirming innovation narrative:

Invest in innovation talent: The leadership team signals a strong commitment to innovation through visible and sustained investments of resources and time. Encourage prudent risk-taking: Innovative companies foster a tolerance for risk throughout the organization by accepting internal cannibalization, endorsing a fail-fast approach, and learning from innovation disappointments. Adopt a customer-centric innovation process: The process used by growth leaders starts with deep insights into customers and anticipates emergent needs. Align metrics and incentives with innovation activity: The innovation dashboard emphasizes learning over scorekeeping and creates a credible link to rewards and recognition for innovation accomplishments.Lever 1: Invest in innovation talent. Innovation is a pursuit that requires intensely creative and tenacious team efforts in the face of frequent setbacks. So it should come as no surprise that of all the levers represented in our surveys, investment in innovation talent best explains growth leadership. This result was reinforced during our in-depth interviews, with statements such as “We can’t promote the best technical people if they don’t know how to manage people and projects” and “Innovation benefits from diversity in the membership of project teams, so you can’t afford to take the easy way out by assigning whomever is available.” Some respondents even noted longer-term benefits for company leadership. One person observed, “You are not just hiring and developing innovation talent — this is a great training ground for senior jobs.”

Unfortunately, our survey also revealed a disturbing lack of attention to and investment in innovation talent: Fully 41% of the respondents said that their companies do not make it a priority. As the CMO of a large packaged goods company that missed the emerging market in organic gluten-free foods ruefully told us, “We put our best people on our biggest brands to protect earnings, and everyone gets the message.”

Progress on the innovation talent challenge begins with the CEO making the chief human resources officer (CHRO) a strategic partner. With the right CHRO taking a lead role, the leadership team can begin addressing questions such as the following:

Are we considered an employer of choice by the people we want to hire? What is the retention rate for our top innovation talent, and how can we raise it? Are headhunters trying to recruit our innovation talent? If not, what does that tell us?Senior executives also need to pay special attention to nurturing the team leaders, project directors, and program managers who champion and lead innovation initiatives. In that spirit, one manufacturing company studied its best innovation leaders — conducting lengthy interviews guided by “critical incident” questions, such as “What was your biggest success and your greatest failure, and how did they come about?” — to identify the competencies that distinguished high performers. Traits that were deemed difficult to develop, such as conceptual thinking and a consistent focus on end-user needs, became the basis for recruiting and selecting new talent; traits considered easier to develop, such as technical product knowledge and presentation skills, were incorporated in training.

Lever 2: Encourage prudent risk-taking. All leadership teams harbor anxiety about the prospects for their innovation initiatives — after all, sure bets on innovation are rare. But how companies deal with this uncertainty is an important factor that separates growth leaders from laggards. The uncertain payoff from investments in innovation initiatives can be paralyzing for growth laggards, who were among the 64% of respondents who identified their companies as highly risk averse; but it energizes growth leaders, who embrace it as an opportunity.

We found three major differences in their approach to risk-taking. First, growth leaders are convinced that more can be learned from the careful dissection of failures than from successes. They routinely conduct innovation postmortems, whereas laggards and average performers do not, forgoing much potential for improvement. Second, growth leaders are more willing than other companies to share the risks and rewards of innovation with their development partners. The mantra of “share to gain” also extends to the way leaders distribute project risk internally, by sharing accountability up and down the organization. Third, growth leaders are more likely than other companies to contain and manage innovation risks by making small, staged bets. They take cues from startups and employ concepts such as rapid prototyping, frugal experimentation, and lean methodologies.7

Lever 3: Adopt a customer-centric innovation process. “Rather than ask what we are good at and what else can we do with that skill, you ask, Who are our customers? What do they need?” says Jeff Bezos of Amazon’s innovation process. “And then you say we’re going to give that to them regardless of whether we currently have the skills to do so, and we will learn those skills….”8 Our results confirm the effectiveness of an Amazon-like customer-centric innovation process: Growth leaders were much more likely than other companies to say that all of their senior managers were attuned to the voice of the customer.

The four bipolar scales shown below, measuring the extent to which each company in our research sample applied the corresponding innovation lever, illustrate key differences between organic growth leaders, growth laggards, and average performers. These three dependent-variable groups were identified by a cluster analysis.

Source: Authors’ survey of executives, directors, and innovation practitioners in 192 companies.

Growth leaders start their innovation process by stepping outside the boundaries of the company. They seek answers to questions such as How and why are our customers changing? What new needs do they have? How can we help them solve their problems and become more successful? What emerging competitors will appeal to these customers?

This is not to say that growth leaders are making a trade-off between an outside-in (what’s needed) and an inside-out (what’s possible) approach to innovation.9 Rather, they are seeking to converge on the best growth opportunities from both directions. The perspective of the customer opens the innovation aperture of the company and helps it avoid the myopia that often accompanies technology-driven approaches to innovation. While, to paraphrase Steve Jobs, customers can’t always tell you what they want, they can be extremely eloquent when describing the problems they face, the frustrations they have to overcome, and why they prefer one supplier over another.10

Growth leaders connect what’s needed with what’s possible. Witness James Dyson and his innovative vacuum cleaners. Consumer studies revealed a lot of frustration with the way upright units quickly lost suction when the disposable bags became clogged with dirt particles. Yet vacuum cleaners were made that way for a century, until Dyson found a solution with a novel design, enabled by high-strength materials, that used centrifugal force to separate dirt from air.

Lever 4: Align metrics and incentives with innovation activity. Most leadership teams lack confidence in the measures tracked in their innovation dashboards; hence, they don’t connect individual and group incentives to innovation activity. The main cause of this distrust is the paucity of metrics. Long-term output, or “tailpipe” measures, such as percentage of sales from products launched in the past three years, are too far removed from day-to-day innovation activities to be useful motivators. And most companies do not track innovation metrics related to nearer-term results, or “input” measures, such as process effectiveness, leadership commitment, or competency development.

But we find that input measures are what growth leaders emphasize in their innovation dashboards. These metrics reveal a variety of insights, such as loose screening processes that leave poor ideas in the innovation pipeline for too long, sloppy development processes that cause delays in hitting project stage gates, and poor product quality that requires recycling innovations back through the development stage.

In 2013, Philadelphia-based Thomas Jefferson University and its associated health system, Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals, decided to hire a new president and CEO, one dedicated to innovation and organizational transformation throughout the 194-year-old institution. When Dr. Stephen Klasko arrived, he used focus groups, town halls, and email contests to enlist roughly 1,000 of the health system’s employees in the development of an organizational narrative that put innovation front and center. Here’s how Klasko articulated that narrative in an interview with us:

We will innovate to bring care and caring to where the patient is. We will become an entrepreneurial health organization, bringing creativity, passion, and flexibility along with the more traditional academic medical center skill sets of strategy, focus, and discipline…. Thomas Jefferson University will concentrate on emerging health professions — it will provide the people needed in health care 10 years from now.

In addition to helping the health system envision a new narrative, Klasko explained to us, how he, in effect, sought to make it manifest by pulling the four levers of innovation.

Invest in innovation talent: Klasko filled multiple senior posts, which had been purposely left open by the board, with executives committed to innovation. He also appointed a new leader for what he calls the center’s “strategic pillar of innovation,” who is one of his four functional direct reports. And he established an ongoing, yearlong executive education program for high-potential employees, which equips the next generation of leaders with tools for managing rapid change and encourages innovative, cross-department thinking.

Encourage prudent risk-taking: “We need to think about what is going to be obvious 10 years from now and start doing it today, which means we have to take risks,” says Klasko. He also signaled an acceptance of failure by grading his own performance as below average in four of nine identified areas during his first “State of the Union” address as CEO.

Adopt a customer-centric innovation process: To make sure the health system is hearing the voice of the customer, Klasko told us, he plans to hire a new CEO of Patients in 2019. The system conducts patient focus groups and town halls to better understand patient needs. It also engages in “hotspotting” — the strategic use of data to identify, understand, and better serve high-needs patients, so they can eventually become less reliant on acute care settings such as emergency rooms.

Align metrics and incentives with innovation activity: Klasko has tied compensation, including his own, to innovation performance. In addition, the health system has instituted a variety of innovation-based incentives, including naming two faculty members as “entrepreneurs in residence” annually and providing each with $150,000 in funding for far-future programs, hosting innovation hackathons with cash and business-planning prizes that draw interdisciplinary teams from across the institution, and awarding all Jefferson patent-winners with membership in the National Academy of Inventors, among other programs.

The new innovation narrative appears to be paying off. The hospital system expanded its top-line revenue from $1.5 billion in 2014 to $5.1 billion in 2018, and Klasko and Bruce Meyer, president of Jefferson Health, tell us that it has achieved organic growth of approximately 5% annually in outpatient revenue and 2% to 3% annually in inpatient revenue over the past five years. A pending merger with Einstein Health Network will mark the beginning of a long-term effort to redesign care delivery for underserved markets. IBM Watson selected Jefferson Health as the first academic medical center in its IoT smart hospital rooms initiative, and that led to the development of a specialty telehealth product called JeffConnect. Meanwhile, Thomas Jefferson University has attracted a number of major donations with its vision of innovation, among them a $110 million gift from the Sidney Kimmel Foundation. Klasko himself was named one of the Most Creative People in Business in 2018 by Fast Company — the only hospital executive so recognized.

Whirlpool, for example, has a real-time innovation dashboard that any manager can use to track new concepts in process, which part of the globe they are coming from, and how many are headed for commercialization. And Whirlpool’s leaders pay close attention to these metrics, because roughly 30% of executive compensation is tied to innovation performance — a rare example of incentive-innovation alignment.11

Executives are awash in advice about the need to grow and to innovate — but too much advice can be just as bad as too little. A growth-affirming innovation narrative and the four levers that make it manifest within a company can help leaders focus and prioritize their innovation efforts. The process of identifying and articulating the narrative is essential to understanding the culture of innovation within a company and envisioning what it can achieve. The levers bring that narrative to life. Without them, organic growth leadership in any industry is a hit-or-miss endeavor.

Caiaimage/Andy Roberts/Getty Images

Caiaimage/Andy Roberts/Getty Images A client (who I’ll call “Alex”) asked me to help him prepare to interview for a CEO role with a start-up. It was the first time he had interviewed for the C-level, and when we met, he was visibly agitated. I asked what was wrong, and he explained that he felt “paralyzed” by his fear of failing at the high-stakes meeting.

Digging deeper, I discovered that Alex’s concern about the quality of his performance stemmed from a “setback” he had experienced and internalized while working at his previous company. As I listened to him describe the situation, it became clear that the failure was related to his company and outside industry factors, rather than to any misstep on his part. Despite that fact, Alex could not shake the perception that he himself had not succeeded, even though there was nothing he could have logically done to anticipate or change this outcome.

People are quick to blame themselves for failure, and companies hedge against it even if they pay lip service to the noble concept of trial and error. What can you do if you, like Alex, want to face your fear of screwing up and push beyond it to success? Here are four steps you can take:

Redefine failure. Behind many fears is worry about doing something wrong, looking foolish, or not meeting expectations — in other words, fear of failure. By framing a situation you’re dreading differently before you attempt it, you may be able to avoid some stress and anxiety.

Let’s go back to Alex as an example of how to execute this. As he thought about his interview, he realized that his initial bar for failing the task — “not being hired for the position” — was perhaps too high given that he’d never been a CEO and had never previously tried for that top job. Even if his interview went flawlessly, other factors might influence the hiring committee’s decision — such as predetermined preferences on the part of board members.

You and Your Team Series Learning Learning to Learn

Learning to Learn In coaching Alex through this approach, I encouraged him to redefine how he would view his performance in the interview. Was there a way he might interpret it differently from the get-go and be more open to signs of success, even if they were small? Could he, for example, redefine failure as not being able to answer any of the questions posed or receiving specific negative feedback? Could he redefine success as being able to answer each question to the best of his ability and receiving no criticisms about how he interviewed?